The news is full of stories about the chaos in Egypt, and the coverage has been dominated by images of violent conflict. When I saw these pictures, it was hard not to think about all the people who had died during the uprising that brought down former President Mubarak.

These events have thrust Egypt into a period of great uncertainty, and they have made it difficult to focus on anything else. But even amid all this violence, one of my favorite museums here in New York has been doing something remarkable: It has put on an exhibit that celebrates Egyptian culture at its highest level, and it has done so in a way that honors the sacrifices of Egyptians who fought for a better future.

The exhibit is called “The Treasures of Egypt,” and it is on view now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is an extraordinary collection of ancient artifacts from Egypt’s past. As you enter the exhibit, you are surrounded by dozens of these objects, which were made between 3200 B.C. and 30 B.C., when Egypt was ruled by Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander the Great’s generals who took control after Alexander’s death.

Not long ago, such an exhibit would have been unimaginable in Egypt; such objects were too important to be shown

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) is a Manhattan art museum that was founded in 1870 by a group of American citizens. It is the largest art museum in the United States, and it receives almost 5 million visitors annually. The Met has been open since its first location on Fifth Avenue and 82nd Street; this is where all of its main paintings, sculptures, and works of decorative art are displayed. However, it also has branches in Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island.

The Met is currently celebrating its 125th anniversary. As part of the celebrations, they have begun an exhibition of Egyptian antiquities from their permanent collection. This exhibit runs until May 12th, 2012 and is titled “Orb: The Glory of Egypt.” The title refers to the winged globe that represents the sun god Ra. In addition to many other artifacts from ancient Egypt, there are two mummies on display and one of these mummies has been identified as Pharaoh Nesperennub’s daughter Nesitanebetashru.**

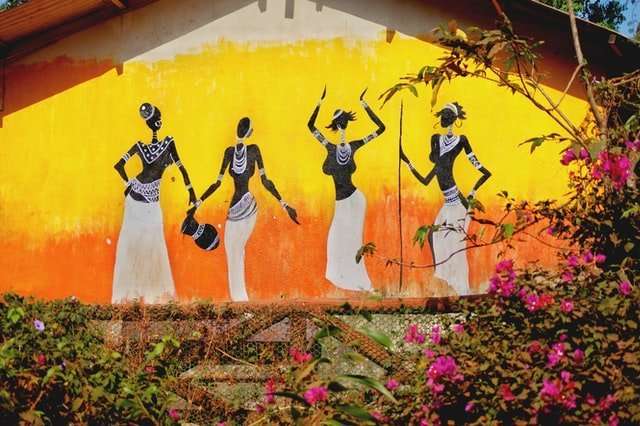

Here’s a piece of art that’s usually not to my taste, but it is lovely.

Here’s a group of people who were clearly having fun. And here’s one that looks like a good time was had by all—except for the fact that the artist has obliterated everyone’s faces, including his own.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) in New York City is exhibiting ancient Egyptian treasures. The show’s title—The Treasures of Egypt: Ancient Masterpieces from the Collection of Jordan*—seems to imply that the museum owns these treasures, but it doesn’t. The Met simply has lent them for public display and that makes this exhibit unique. Most of these objects are not normally available for viewing by the public.*

The Met began collecting Egyptian antiquities in 1872 when it bought an alabaster vase dated to 943 B.C., a year after the opening of the Suez Canal. That same year, an Egyptian named Ahmed Sami went to Paris and sold a 1,000-year-old bronze statuette to the Louvre for $500. It now sits in storage because its present location must be kept secret.*

There is nothing particularly new about Egyptology, which is nothing more than archae

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibit, “The Treasures of Egypt: Art from the Collection of the Musée du Louvre,” is the result of a collaboration between the Met and its Parisian counterpart, which was organized in two parts. The first took place from 2004 to 2006, when curators from both museums visited each other’s collections to select objects they would like to see juxtaposed with their own. They then worked together to create “The Splendor of Ancient Egypt: Art from Cairo and London,” a three-part traveling exhibit that opened at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, in October 2005 and ended its run at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in February 2007.

Due to popular demand, the joint venture was expanded into an even more ambitious project, with the Louvre sending a selection of its treasures—95 objects chosen by Danielle Cohen-Levinas and Jean-Luc Martinez—to New York for an extended stay. The Met reciprocated by sending another 95 examples of its Egyptian art—all but two were previously at the museum—which it organized around a similar theme as well as around individual works that had never before left New York. In addition, the Louvre contributed $4 million toward a new wing for Egyptian

A nd so we have the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibit, “Egypt: Ancient Treasures from the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” This time around, Egypt is being celebrated for its artistic treasures rather than for its political influence. The exhibit displays objects that range from 4,000 to 30 B.C., reflecting Egypt’s incredibly long and complex civilization, which was in a continual state of change.

The artworks on display are drawn from the Metropolitan Museum’s collection and span many periods and styles. Some objects are accompanied by reproductions of ancient texts; others by only a few words. Looking at this textless piece, I wondered what it represented and why it was made:

(Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

It would appear that Ramses II has been transformed into a falcon-headed god. However, he is not Horus — he is Ra-Horakhty, who combined the features of Ra (the sun god) and Horus (son of Osiris). The winged globe held in his hands symbolizes both the sun and the primordial mound from which Ra-Horakhty emerged at creation. Like other Egyptian gods, Ra-Horakhty embodies not only the creative force but also the power to govern and maintain.

It is a relief to be told that the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibit, “The Treasures of Ancient Egypt,” is not just another parade of royal funerary trappings.

The new exhibit, which runs until April 13th, is subtitled “A Portal to an Ancient World,” and it is. It presents something more than just a succession of dazzling artifacts. It represents a way of understanding the ancient world that can serve as a model for how we understand our own.

Telling stories about history always involves a good deal of argument and speculation, but at its best it also reveals something real about the past—about how people thought and felt, what they valued or feared, what they did and why. Such reflections can also tell us something true about ourselves. History is after all a record of human experience from which we have much to learn.

The new exhibit does not simply present a series of objects in chronological order and then leave it at that. It organizes the objects—a few dozen mummies and sarcophagi, steles and statuary, jewelry and dice—to suggest ways in which different periods of ancient Egyptian history influenced one another, connecting across time periods that are often seen as distinct from each other. The exhibit’s mood

The three figures on the throne were originally life size and colored. They were first discovered in 1913, when a farmer found them in a tomb called the Red Pyramid ( Djoser ) at Saqqara about twenty miles south of Cairo. The tomb was built for a king named Sekhemkhet, who ruled Egypt from 2667 to 2648 BC.

Tutankhamun’s tomb, which was found in 1922, had many objects made of gold and other precious materials that were removed by his family and placed in other tombs. His stone sarcophagus was too small for his mummy, so he was re-interred in this tomb with four gilded wooden statues of himself. These figures are part of a larger collection of funerary art and artifacts from the tomb of Tutankhamun that are now on loan to the Metropolitan Museum in New York City.