If you are an artist, the news is often bad. You have to learn how to frame whether the news is bad or good if you are an artist.

In The Wake Of The News: How to frame whether the news is bad or good if you are an artist. Series supporting portfolios of artists.

When I saw the cover of the latest New Yorker, I thought it might be a painting by Edward Hopper or James Ensor, but it turned out to be a photograph by Christopher Anderson. It was his second appearance on the cover of the New Yorker in a year. Compare that with what other photographers would consider a banner year—the cover of Rolling Stone once or twice, maybe Vanity Fair—and you can see how he’s been doing lately.

These are the rules that artists have always used to frame whether the news is bad or good if you are an artist. They are not moral rules: they are about how to make art.

Rule 1. The artist’s job is not to solve problems, but to deepen them.

Rule 2. The journalist’s job is not to inform, but to startle.

Rule 3. A picture is not worth a thousand words, it’s worth at least 10,000 words and an argument.

Rule 4. The first draft of history is written by the winners, and it’s rarely the final draft that matters most to artists.

Rule 5. The more art tries to look like science, the more it risks looking like a sermon.

Rule 6. Journalists have obligations that artists don’t have: they must be fair, balanced and objective (or as close as humanly possible). Artists have only one obligation: to be true.*

The news is bad for artists. That is what the headlines usually say, anyway. And it isn’t strictly true. The news isn’t bad for all artists and it isn’t bad for all of the time. There are seasons for art and those seasons affect which kinds of news are good and which are bad for artists.

For example, if you are trying to get your work into a museum show, having a show at another museum nearby that people have heard of will be a help to you. On the other hand, being in a really hot gallery that everyone wants to go to will make it harder for you to get in elsewhere. When you are building your reputation, early shows are more important than late ones; when you have built a reputation, late shows can be better because they have more impact.

The news is also not always bad or good. It depends on what kind of artist you are trying to be and on how you decide to frame whether the news is good or bad. If art is supposed to be “transformative,” then many kinds of criticism will seem like good news: it means that something new has been created that changes things. If art is supposed to be “critical” then negative reviews will be seen as good: they mean that someone

When you buy a work of art, you are making a statement about the world and your place in it. When you buy a work from an artist with a track record, you are making an investment that may or may not pay off. When you buy a work from an emerging artist, you are supporting the future of art.

The artists whose works we represent have been selected because they have something to say and can say it. Collectively their works form a portrait of contemporary life and the way we live now. Some of those lives are not pretty; some are wonderfully uplifting. But all of them are worth considering.*

The artists here do their best work when they can focus entirely on their craft without having to worry about money. That’s why we ask for a percentage rather than flat fees or purchase prices: so that no matter what happens, we have an incentive to make sure our artists succeed.”*

In my experience, the best thing an artist can do today is to buy art. This sounds like a paradox because we live in a world where everyone says that the art market is bad. But the art market isn’t bad for anyone who has anything to sell. The art market is only bad for people who want to buy things they don’t understand and don’t want anyway.

This is why you should care about art fairs, and it’s why I spend so much time talking about them. Art fairs are where the action is — where everyone who has something to sell meets everyone who wants to buy it. Anyone who shows up at an art fair with money in hand and no idea what he wants to buy isn’t looking for good deals; he’s looking for someone else’s money, and he hopes to find it by acting clueless.

The good news for artists is that this kind of person isn’t interested in your work. The kind of person who buys at art fairs is looking for something specific, and not just anything will do. You see this at every level: the collector might not be sure what she wants — but she knows it when she sees it. And she can afford to walk away if she doesn’t find it.

That’s

There are two main ways to approach the “market” for art: you can try to sell your art, or you can try to be an artist. The first goal is much more likely to make you rich, but if it does, it will probably also make you miserable.

The second goal is almost guaranteed to make you a lot happier, but it has a better chance of making you poor. Happier and poorer.

Being a writer, I am biased in favor of the second option. I have seen many writers who were rich and miserable, and many writers who were poor and happy, but I’ve never seen any writer who was both rich and happy. But most artists are not writers; they need to deal with the market directly as well as indirectly through their work.

So here’s my advice on how to get rich while being an artist: don’t.

That is only half-serious; of course there are some artists who have gotten rich (although not by selling their art). My point is that the way you get rich by being an artist is not what most people would think. There is no magic trick, no certain way of packaging your art so that it sells like hotcakes when all those other hotcakes are selling cold pancakes instead.

Artists are often asked, “How do you respond to bad reviews?”

The question is usually worded that way because it assumes an easy answer: “If the review is good, ignore it. If the review is bad, feel bad.”

The questioner wants to know how artists can maintain a healthy attitude in the face of such assaults. The assumption is that artists should be able to keep their head about them and not get too worked up about what critics say.

As one of the few art critics who comes from a visual arts background, I think this is a rather naive attitude. One of the things that makes art so interesting is that its value is subjective. Artworks compete for attention among millions of other pieces of information in the world; they have to be compelling if they are going to compete at all. They have to demand attention if they are going to get it.

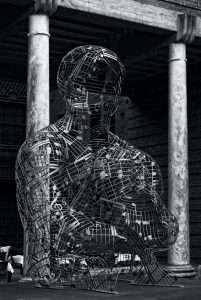

Image: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain was rejected by the Society of Independent Artists when he submitted it in 1917. (Artwork: Ken Reid)

Aesthetically speaking, I find Fountain beautiful and hilarious. But most people don’t see it that way; they take offense at what they perceive as its vulgarity, and the fact that Duchamp made the piece